by Paul Martin

Thursday, September 14. A text from my phone reads, “Hello Andrea. Jonathan Alpeyrie sent me your contact information. We met this week in New Mexico. I am working in the very precarious area of Española on the fentanyl crisis.”

She responds, “My daughter died in Santa Fe. I’m very familiar with the drug problem.” The following week, we met in DC, along with hundreds of other parents who lost their children to fentanyl.

I call them Monuments of Suffering. Their grief might be our greatest hope. Fentanyl is not just another drug. It is for them that I launched United Against Fentanyl.

Yesterday, we spoke. After our call, she texted me the death certificate.

October 1, 2020. Cause of death: Toxic effects of fentanyl, probable heroin, flubromazolam, alprazolam.

Toxic effects of fentanyl.

“Amanda Paige. We called her Mana. Amanda knew everybody. Everybody knew Amanda. She also was extremely smart. She was taking college classes while she was in high school. She got a full-ride scholarship to university.”

“I knew she smoked weed in high school. After graduation she had a surgery. They prescribed Oxy.”

“She told me later, ‘Mom, once my pills were gone, I was hooked.'”

Me: “Did you notice any difference when she started taking Oxy?”

“Oh my God, yes. Violent. Disrespectful. Completely changes their personality. For her first few years of college, it was Oxy. Twenty-five bucks a pill. And when the Oxy runs out, they all go to heroin. I learned that years later—all of them.”

“This is before fentanyl, of course.”

(Note. Today, heroin is effectively a thing of the past given the strength, accessibility, and low cost of illicit fentanyl.)

“All I can say is for years, I was living in the insanity of her addiction. It was affecting every single area of my life. Addiction affects the family. Like I have a son who barely talks to me to this day because, for 15 years, I was focused on saving my daughter’s life. Period. I let my marriage slide. I let my relationship with my son slide. I got down to 85 pounds.”

“I learned that not all rehabs are the same. Fifteen thousand dollars a week. And what we got out of it was they prescribed her Suboxone which of course is another opioid. And she was miserable on it—she felt like she wasn’t clean, and she wasn’t. It took two years to wean her off it. But we did with doctor’s supervision.”

“What does she do? The minute she gets off Suboxone? She gets hooked on Xanax.”

“In a way, I don’t think I was tough enough. One night, she was so high. I had to pick her up from a restaurant. Someone had called. They couldn’t get her out. It was two in the morning. I arrive, and she’s in the back booth under the table. We are walking out. I video her. She is so out of it. She couldn’t even walk. And the next day, I sat down with her. I told her I wanted her to see what this was doing to me. I showed her the video. She grabbed the phone and threw it across the room and hit me.”

“At that time, she was doing heroin. And Xanax.”

“The rehabs were revolving doors. She’d get out. She’d do okay for a bit. And she’d relapse. Rehab after rehab after rehab, that was the cycle. And when she came out of the rehab for Xanax, she was doing great. She got back together with an old boyfriend.”

“One day Rick came to me. Our marriage had been tested for years. ‘We need to talk. She either moves out on her own or you and I are finished.’ He’s like, ‘I can’t live like this anymore.'”

“I had to take a real hard look at myself. I had to realize that I was part of the problem. I enabled in so many ways. Maybe I should have let her be homeless. I don’t know. Paul, it’s so hard, I don’t know where to draw the line. I have a husband who is livid with me for letting her live with us so many times. I have a son who was livid with me because for so many years I put her first. He was so easy. He went into the Navy. But I should have given him the attention he needed. This almost ruined my marriage both before and after her death.”

“She reconned with her old boyfriend. She moved to Santa Fe. She was sober.”

“I’m adopted. My two children were my only two blood relatives in the world.”

“I could never get her to seek help for her mental illness. Even though she was mentally ill. I got a call from her. She said, ‘Mom, need to come out there for a while.'”

“I knew she had relapsed.”

“Paul, the night before she died, she called. She was so excited. She was moving into her own new apartment. Rick was home. ‘I’ll do a walkthrough with you on camera.’ We gushed as she showed me everything.”

“The last words I ever said to my daughter was, ‘Amanda, I’m so proud of you and I love your new apartment. But you’re high, and I can’t talk to you when you’re high.”

“It was the next day I got the call.”

“I blacked out.”

“To have her die, Paul. When she died, I didn’t get out of bed for months. I told Rick over and over I need to be committed. I’m going to kill myself.

‘I thought about every single fucking way to kill myself.”

“I decided I was going to take my gun and sit in the bathtub and shoot myself in the head so it didn’t leave a mess for him.”

“He still worked and so he would leave me in the morning. And he would leave my Diet Coke. And he would leave my Diet Coke beside the bed. And he would come home after work and I’d be in that same position. He’d get me up. He’d take me to the bathroom. He bathed me when I needed to be bathed.”

“One time when I told him I need to be committed — like, I don’t want to feel like this anymore, I don’t want to hurt like this anymore, I want to be drugged out and numb. He said, ‘I’ll tell you what, Andi, you say that to me one more time and I’m going to take you. So, say it one more time, and I’m going to take you, and you might not come out the same.'”

“I never said it again.”

“The brewery where she worked at did a celebration for her. There were hundreds of people that showed up. They had it catered. They gave the beer away for free. One of the things that I did, and I really think this was Amanda coming through to me — so I took her ashes. She was just loved by so…everybody loved her. And I had them divided into little containers. So I ended up having her ashes divided up into containers.”

“Hundreds of people took my daughter’s ashes.”

“And I asked them to spread them in their favorite place. Or if they felt like keeping Amanda with them in their house to keep her with them.”

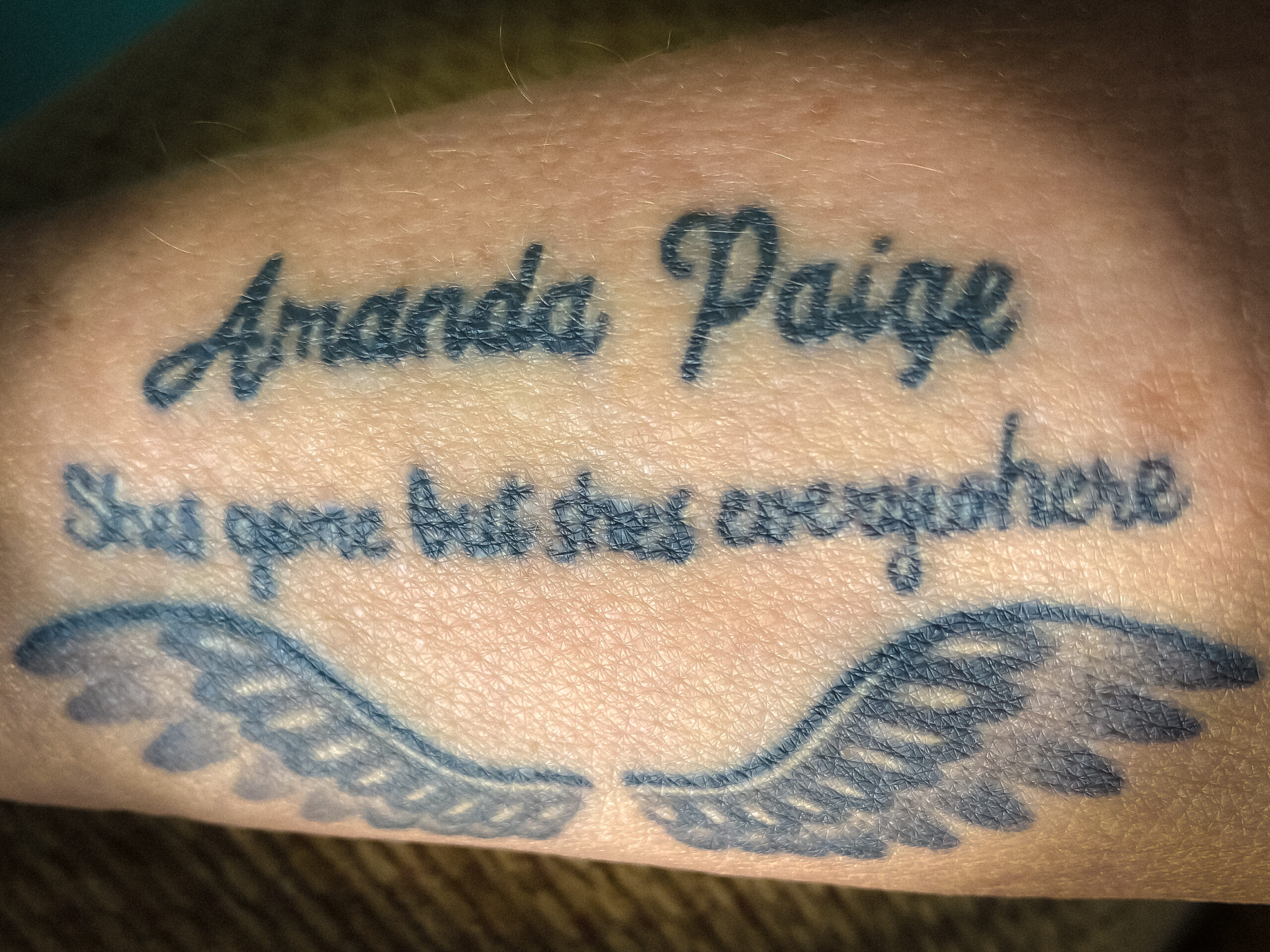

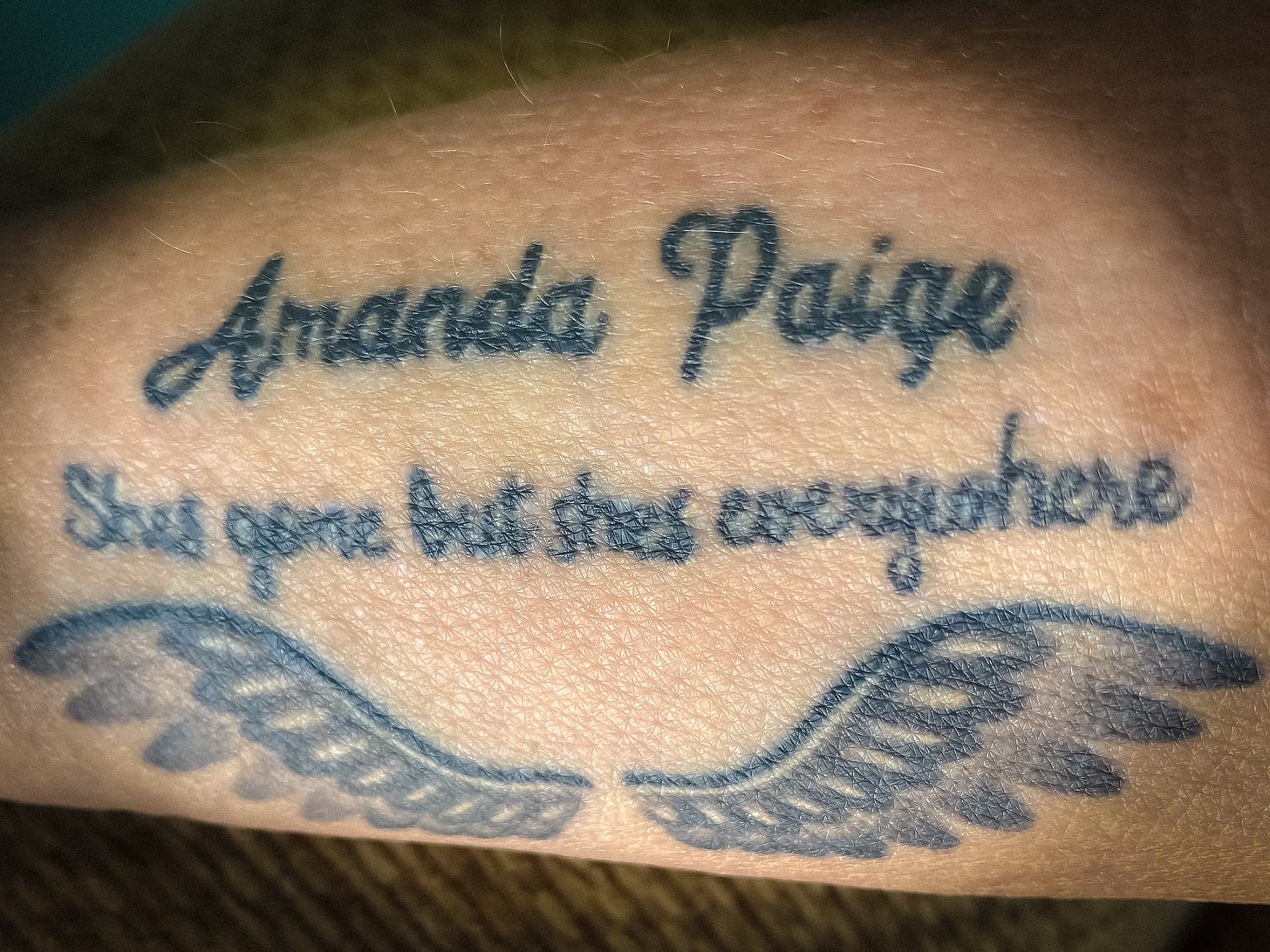

“And I had this tattoo that says, Amanda Paige, she’s gone, but she’s everywhere.”

(Every day, nearly 300 people in the United States die from illicit fentanyl. That number rises each year. Illicit fentanyl is the leading cause of death for those between the ages of 18 and 45. Today, there are tens of millions of fentanyl pills on the streets of America, where they can be purchased for as little as $1 per pill.”