by Paul Martin

“My son—he was different. He was everything we all wish we could live by.”

I heard these words on my latest trip to fight the fentanyl scourge. I left Orange County for Eastern Tennessee, North Carolina, and Washington, D.C. — to listen to more grieving parents, and introduce my new work to federal government leaders.

The time with the parents means the most. Those Monuments of Suffering — I launched United Against Fentanyl for them and their families.

She lost her son in 2022 — the mother from Tennessee. No substance use disorder. No running with the wrong crowd. Lived with his brother.

“They were so close.” (Cries.)

He bought a prescription pill that was not a prescription pill in the end. She drove me to the house where he passed. It was a late spring afternoon when they found him. She showed me the bedroom. The bedroom where his brother desparately pounded on the door. The door he had to break down. The bedroom where he lay, unresponsive.

You can find the pills anywhere these days. The Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) seized 70 million just last year — enough to kill over 300 million Americans. A drug dealer reached out to a 15 year old boy on Snapchat and delivered drugs to him at home. Just a pill. That was the end. At fifteen, Sammy was poisoned.

Today, dozens of families are part of a lawsuit against Snapchat. The lawsuit aims to alert parents when dangerous content is shared through children’s social media accounts, enabling life-saving interventions at critical moments.

Snapchat fights like hell to get the lawsuit dismissed.

Then launches a Superbowl ad calling for “More Snapchat.”

I’ve met dozens of these parents in the past year. They are thousands spread across a nation caught flat-footed by the fentanyl crisis, the crisis the Mexican cartels planned in 2013 while boasting of creating “streets full of junkies” across our country.

How to describe the pain I saw while she showed me that house and while we ate lunch later that day? I can get rational and refer to Khubler-Ross’s Five Stages of Grief: denial, depression, anger, bargaining, and acceptance. Sure, you see these in their demeanor.

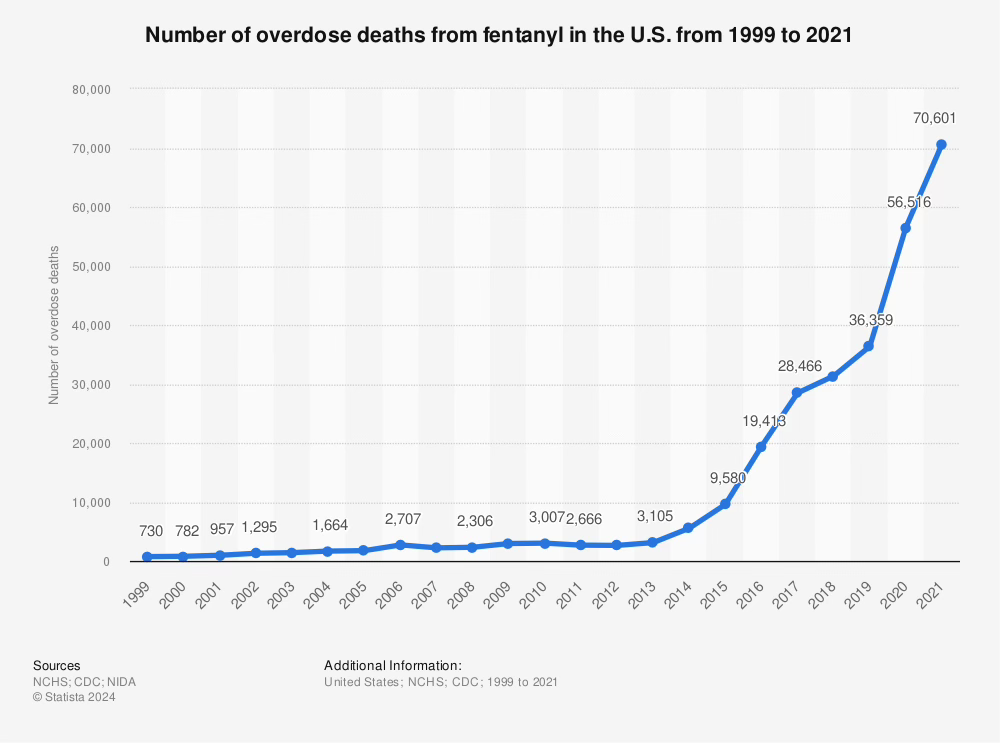

Or I can go to the data. There are so many statistics to cite about this American scourge. Two hundred die every single day from fentanyl, the leading cause of death for 18-45-year-olds, with more dead each year than in the Vietnam, Iraq, and Afghanistan wars combined. Numbers matter.

However, stages of grief and more data bring about the obscuring of humanity.

And when it’s your child. In February, one mother’s anguish was so great after losing her son to fentanyl poisoning that she took her own life. I’m out; I can’t endure it anymore.

A day later, in North Carolina. To have dinner with a grieving father. The one who lost his son to a vaping pen. Later that night, he texted me a photo of the entire family, with his deceased son on the far right, smiling. Happy. Normal kid.

Our next stop is Ashville, North Carolina, to get gas. Our board member, Jason, is with me. We are looking for a Starbucks. We enter a Fresh Foods market. Apple Maps took us there — to the Starbucks inside the store.

Jason asks the cashier if she knows much about drugs. The teenager shoots a nervous nod. “What about fentanyl? Do you know about that?”

“Yes, my mother is an addict. Her life after fentanyl is unrecognizable. She just disappears and we don’t know where she goes.”

We were waiting for our lattes. Jason walked away. The barista, another teenager — almost in a whisper — asked if we were talking about fentanyl.

“Do you know about fentanyl? I am launching a national organization to help save lives from fentanyl.”

“Yes, my stepmother died from a fentanyl overdose last year.”

We chat for a few minutes. I get the coffees. Walk over to Jason, who is speaking with the security guard. I listen.

The security guard to Jason, “My son lives in Ohio. I don’t see him. He’s addicted to fentanyl.”

A mother loses her son to a fake pill.

A father loses his son to a vaping pen.

A teenager whose mother is addicted.

A teenager loses her stepmother.

A father with an estranged son.

All from fentanyl.

We are in D.C. now, meeting with the leaders of SAMHSA—the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration, a part of the Department of Health and Human Services. This 18-story building is filled with hundreds of civil servants tasked with bringing services and results to communities across all 50 states.

Many today have disdain for government, especially our institutions. Not me. Yes, federal agencies are massive machines and need reform. But take them away — Health and Human Services, Justice Department, Transportation, Defence — and we colapse as a nation.

I share a graph with an expert.

“In the next few years we will hit a quarter of a million deaths, I believe.”

She nods.

I go on.

“We’ve gone from 5,000 to 80,000 in less than a decade. We can’t control the supply from legal ports of entry. We can’t control substance abuse or the mental health crisis. We can’t control the tens of millions of counterfeit pills already in the country. We can’t control the proclivity of young people to experiment.”

She continues to nod.